An anal fistula (fistula-in-ano) is the result of an anal abscess, occurring in up to 50% of patients with abscesses. Occasionally, these glands get clogged and can become infected, leading to an abscess. The fistula is a tunnel that forms under the skin and connects the infected glands to the abscess, but a fistula can be present with or without an abscess. Other situations that can result in a fistula include Crohn’s disease, radiation, trauma and malignancy.

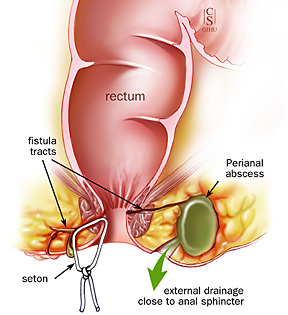

Occasionally, bacteria, fecal material or foreign matter can clog the anal gland and create a condition for an abscess cavity to form. After an abscess drains on its own or has been drained, a tunnel (fistula) may persist. This typically involves some type of drainage from the opening. If the opening on the skin heals when a fistula is present, a recurrent abscess may develop.

SYMPTOMS AND DIAGNOSIS OF ANAL FISTULA

A patient may have pain, redness or swelling in the area around the anal area. Fatigue, general malaise, as well as accompanying fever or chills are also possible. In addition, irritation of the perianal skin or drainage from an external opening may also be present.

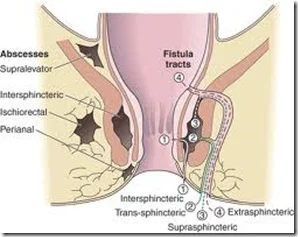

Most fistula-in-ano are diagnosed and managed on the basis of clinical findings. Occasionally, additional studies such as ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI can assist with the diagnosis of deeper abscesses or the delineation of the fistula tunnel to help guide treatment.

SURGICAL TREATMENT

Initially if an abscess and fistula are present, the treatment of an abscess is surgical drainage, under most circumstances. An incision is made in the skin near the anus to drain the infection. This can be done in a doctor’s office with local anesthetic or in an operating room under deeper anesthesia. Hospitalization may be required for patients prone to more significant infections such as diabetics or patients with decreased immunity.

Antibiotics alone are a poor alternative to drainage of the infection. Although surgery can be fairly straightforward, it may also be complicated, occasionally requiring staged or multiple operations. The surgery may be performed at the same time as drainage of an abscess, although sometimes the fistula doesn’t appear until weeks to years after the initial drainage.

If the fistula is straightforward, a fistulotomy may be performed. This procedure involves connecting the internal opening within the anal canal to the external opening, creating a groove that will heal from the inside out. This surgery often will require dividing a small portion of the sphincter muscle which has the unlikely potential for affecting the control of bowel movements in a limited number of cases.

Other procedures include placing material within the fistula tract to occlude it or surgically altering the surrounding tissue to accomplish closure of the fistula, with the choice of procedure depending upon the type, length, and location of the fistula. Most of the operations can be performed on an outpatient basis, but may occasionally require hospitalization.

Pain after surgery is controlled with pain pills, fiber and bulk laxatives. Patients should plan for time at home using sitz baths and attempt to avoid the constipation that can be associated with prescription pain medication. However, despite proper and indicated open or minimally invasive treatment, both abscesses and fistulas can potentially recur.